Birch Homestead also has architectural value because its component parts are all representative building types of their period and functions. It is special because construction of the house marked the beginnings of European settlement of the Upper Rangitikei high country area, and it is the area’s oldest building. The homestead buildings also have considerable local historical value because of their association with the Birch brothers and other well-known Hawke’s Bay and Rangitikei people.

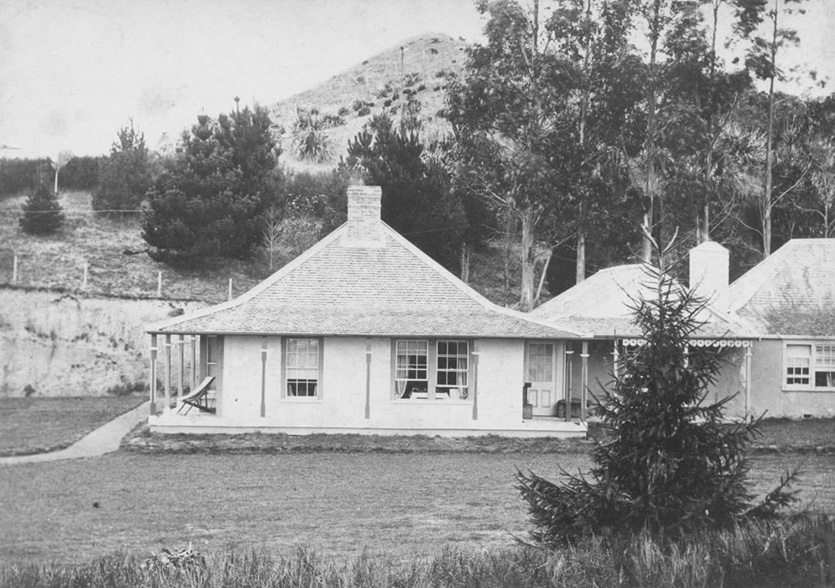

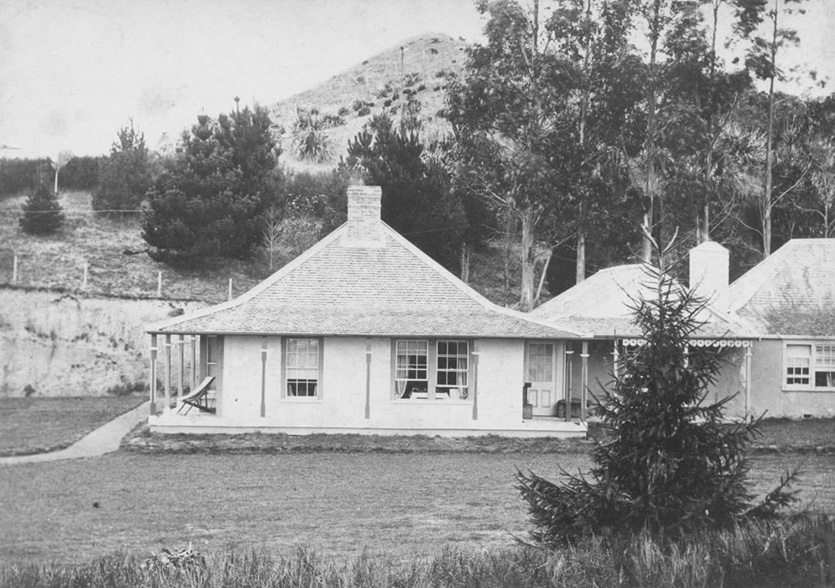

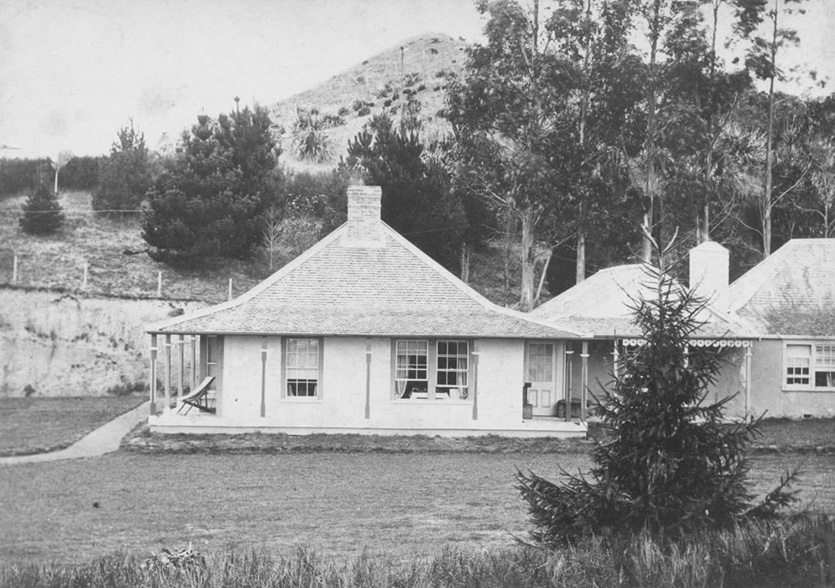

The Birch brothers, Captain Azim Salvatore (1837-1923) and William John (1842-1920), immigrated to Hawke’s Bay from England separately in the early 1860s. In 1867 they began negotiating with local Maori to lease a sheep run in the Kaimanawa-Oruamatua Block, initially known as Erehwon. They then built a house using what is thought to be cob, a material created from dried clay, straw, and dung. Cob was a popular construction material among early European settlers because it was relatively easy and cheap to make and use. This was used in the house’s three sections, linked together by roofing the spaces between. The northern part is the largest section and is a typical English Colonial double box cottage, with a hipped roof, verandahs, and two rooms either side of a passage. The other sections form a line to the south, and it is probable that the middle section was the original construction. Close by are late nineteenth century timber outbuildings associated with the homestead’s domestic activities.

Estrangement saw the Birch brothers’ successful station split between them in 1897. Azim retained the homestead portion and renamed the farm Oruamatua. Dating from this time are the homestead’s timber and corrugated iron shed, blacksmith’s workshop, and stables. When Azim retired, the property was taken on by eminent Hawke’s Bay racehorse breeder Thomas Lowry (1865-1944) and his brother-in-law Edward Watt. At this time Oruamatua consistently ranked among the top producing sheep farms in the county. Later, Lowry and Watt’s station manager, Frederick Randall Cottrell, purchased the subdivided homestead portion of the farm. His descendants have continued to farm Oruamatua, although they have not lived at the homestead since the 1960s.

Location

List Entry Information

Overview

Detailed List Entry

Status

Listed

List Entry Status

Historic Place Category 1

Access

Private/No Public Access

List Number

2736

Date Entered

29th August 2013

Date of Effect

29th August 2013

City/District Council

Rangitīkei District

Region

Horizons (Manawatū-Whanganui) Region

Extent of List Entry

Extent includes part of the land described as Pt Lot 2 DP 6088 (RT WN418/187), Wellington Land District and the buildings known as Birch Homestead thereon. These include the cob homestead and its three timber outbuildings immediately to the south, as well as the farm buildings to its east being the shed, blacksmith's workshop and stables. (Refer to map in Appendix 1 of the registration report for further information).

Legal description

Pt Lot 2 DP 6088 (RT WN418/187), Wellington Land District

Location Description

Birch Homestead is in the hill country east of Taihape, approximately 7 kilometres northeast of Moawhango on the Taihape-Napier Road.

Status

Listed

List Entry Status

Historic Place Category 1

Access

Private/No Public Access

List Number

2736

Date Entered

29th August 2013

Date of Effect

29th August 2013

City/District Council

Rangitīkei District

Region

Horizons (Manawatū-Whanganui) Region

Extent of List Entry

Extent includes part of the land described as Pt Lot 2 DP 6088 (RT WN418/187), Wellington Land District and the buildings known as Birch Homestead thereon. These include the cob homestead and its three timber outbuildings immediately to the south, as well as the farm buildings to its east being the shed, blacksmith's workshop and stables. (Refer to map in Appendix 1 of the registration report for further information).

Legal description

Pt Lot 2 DP 6088 (RT WN418/187), Wellington Land District

Location Description

Birch Homestead is in the hill country east of Taihape, approximately 7 kilometres northeast of Moawhango on the Taihape-Napier Road.

Historic Significance

Historical Significance or Value Azim Salvatore Birch and his brother William John were the first European settlers in the high country district of Rangitikei, known as Inland Patea. Birch Homestead, constructed from 1868, enabled them to begin developing their leased sheep run, Erehwon. From this time the area gradually became characterised by sheep farming, and still is. Therefore, Birch Homestead has considerable historical importance as evidence of the beginnings of the landscape’s transformation for commercial agricultural activities. The Birch family connection to the homestead also contributes to its historical value. The Birch family have substantial local significance because of their early and longstanding successful involvement in the farming sector. However, Azim was also a prominent figure within the Rangitikei and Hawke’s Bay communities through his lengthy role as a Hawke’s Bay Borough councillor and other avenues, such as the being on the Patea Road Board. Built as a result of the original Erehwon station’s division between the two brothers, the farm buildings also have local historical significance as they are directly associated with the new Oruamatua station of Azim Birch, but also symbolic of the wider regional trend for subdivision around this period. By the 1920s most of the early large runs had been subdivided, which was encouraged through Government policy. Indeed, Oruamatua was subject to further subdivision in the early twentieth century. As part of the landholdings of Thomas Lowry and Edward Watt from 1905, Birch Homestead also has value because of its association with these two affluent and important Hawke’s Bay landowners, both of whom were nationally successful racehorse breeders. Oruamatua remained one of the most productive sheep farms in the region under Lowry and Watt. During their tenure Frederick Randall Cottrell was station manager and since 1920 that family have owned and worked the farm, becoming a well-known family in their community.

Physical Significance

Architectural Significance or Value Birch Homestead’s house is a rare remaining New Zealand example of a relatively large cob house. Cob was a popular construction material used in the early period of European settlement, particularly in areas where timber was scarce. This form of construction used easily accessible materials including clay, straw and dung - making it a reasonably cheap option which required little skill and so could be used for self-builds. More common in the Nelson, Marlborough, and Canterbury regions, this is an especially rare example of cob construction in the North Island and could be unique in the Rangitikei/Hawke’s Bay context. The house’s main block also has considerable architectural value as a characteristic English Colonial double box cottage. This medium sized rural residence, dating from the 1860s, features four rooms off a central passage, a hipped roof and a verandah, all typical of the period. The house’s sequential nature is also characteristic of contemporary residences which were commonly expanded as required and as resources allowed. When considered as part of this group of homestead buildings, the nearby 1897 farm structures also have some local architectural importance indicating the greater availability of timber in the district by this time due to increased transport options. Like the domestic buildings, the stables and shed buildings are representative examples of their respective building types.

Detail Of Assessed Criteria

(a) The extent to which the place reflects important or representative aspects of New Zealand history The Birch brothers are representative of many early European settlers who came to New Zealand for a fresh start and the promise of advancement opportunities. Growing from humble beginnings, Birch Homestead is indicative that with hard work and astuteness this promise could indeed be fulfilled. The dominance of agricultural and horticultural industries within the national and regional economies of New Zealand has been a characteristic since the early period of European settlement. Birch Homestead is contemporary with, and the oldest remnant of, the establishment of commercial sheep farming in the Upper Rangitikei/Inland Patea district, which remains a distinguishing feature of the area. The leasing of large tracts of land from Maori owners to European settler farmers was a common practice in New Zealand and began being implemented at Inland Patea in the late 1860s. This arrangement persisted at Erehwon for decades after its establishment in 1868. The ensuing Native Land Court proceedings and dealings in regard to Kaimanawa-Oruamatua Block, where Birch Homestead is located, is indicative of the flaws and difficulties inherent in that system. (c) The potential of the place to provide knowledge of New Zealand history Because Birch Homestead dates from 1868 it is associated with the earliest period of European settlement in the Upper Rangitikei. As such the site is of archaeological significance. The homestead, with associated domestic and farm buildings, has potential to contain subsurface archaeological deposits which could add to knowledge of domestic and farm life associated with this period. Sub-surface evidence could include early domestic, garden, and farm structures, as well as household refuse. (i) The importance of identifying historic places known to date from early periods of New Zealand settlement Birch Homestead is well documented as the earliest remnant of European settlement in its high country farming district, and the house is the oldest local building. Because of its high level of authenticity, the residence has the potential to provide information about building materials and techniques from this period. (j) The importance of identifying rare types of historic places Cob construction was a characteristic form in several regions of New Zealand in the early period of planned European settlement. However, cob, and other earth construction, dwellings from this period are now comparatively uncommon, and few surviving cob buildings have been identified in the North Island. Therefore, the Birch Homestead’s house is a rare remnant of this once common type of dwelling, which is particularly special because earth construction was not typical in the Hawke’s Bay and Upper Rangitikei area. Summary of Significance or Values Birch Homestead is special as an example of an earth construction house, and is probably cob, which was once a popular building material in early European settler New Zealand. These places are now nationally rare, but exceptionally so in the North Island. Furthermore, this place has importance because the first European settlers to the Rangitikei’s high country region, Azim and William Birch, built it upon arrival there in 1868. The advancement opportunities New Zealand offered in the mid nineteenth century were a key reason for their emigration to the colony and they pursued them successfully, with their sheep station being the foundation of their prosperity. As the centre of these activities, Birch Homestead has special historical importance.

Construction Professional

Biography

Constructed their homestead, Birch Homestead, in Moawhango, from cob in 1868 and made subseqent additions.

Name

Birch, Azim and William

Type

Builder

Biography

Constructed the cob homestead 'Birch Homstead' in Moawhango in 1868 with the Birch brothers.

Name

te Rango, Hiraka

Type

Builder

Construction Details

Description

Initial cob house constructed (now middle section).

Start Year

1868

Type

Original Construction

Description

South section added to cob house.

Finish Year

1878

Start Year

1868

Type

Addition

Description

North section added to cob house and outbuildings constructed.

Finish Year

1897

Start Year

1880

Type

Addition

Description

Shed, blacksmith’s workshop and stables constructed

Start Year

1897

Type

Additional building added to site

Construction Materials

Brick, cob, corrugated iron, glass, timber.

The Moawhango region has long Maori historical associations established when Tamatea-pokaiwhenua (Tamatea land explorer), grandson of the Takitimu canoe’s commander, travelled into the district and claimed it. Within a few generations Tamatea’s descendants came to the region, displacing Ngati Hotu. Following this, Ngati Whitikaupeka migrated there from northern Hawke’s Bay and forced Ngati Hotu out in the mid seventeenth century, with the aid of Ngati Tama and Tanakopiri allies. The ancestor Whitikaupeka was born in this upper Rangitikei area, known as Inland Patea, and upon his return he married and settled there. However, the inland high country between the Kaimanawa and Ruahine Ranges was sparsely populated. This was primarily because of the harsh winter conditions, although local Maori and those from around Hawke’s Bay and Taupo are said to have set up seasonal fishing and hunting camps in the hills. There are two carved houses in Moawhango. The whare called Oruamatua was constructed in the 1870s and nearby Whitikaupeka was built in the closing decade of that century. Missionaries first ventured into the district in the mid to late 1840s, including the Reverend Richard Taylor (1805-1873) in 1845. William Colenso (1811-1899) also passed through the region on his way back to Hawke’s Bay in 1847, but it was not until 20 years later that European settlers began to farm in the vicinity. This region was relatively isolated with the main access to Inland Patea being from the Hawke’s Bay. In the late 1860s brothers Captain Azim Salvator (1837-1923) and William John Birch (1842-1920) came to Inland Patea from the east, along with approximately 4,000 merino sheep. It was the younger of the two, William, who had immigrated to New Zealand first in 1860, from England. This was spurred by the need to carve out a new life after an investment went badly for both William and his father. William settled in Hawke’s Bay acquiring his own sheep and for a time acting as a station manager. Azim’s army career was curtailed because his father could no longer financially support this. Therefore, upon hearing of William’s enthusiasm for the opportunities in New Zealand, Azim followed a few years later and they went into partnership together, farming near Hastings. However, they soon desired to expand their activities. After some exploratory work by Azim, it was in January 1868 that the Birch brothers created their large sheep run northeast of Moawhango by leasing part of the Kaimanawa-Oruamatua Block from Maori. Reportedly the brothers had originally wanted to lease the Owhaoko Block further east. The ownership of the Owhaoko and Kaimanawa-Oruamatua Blocks and related Native Land Court decisions were later contested, and eventually referred to Premier Robert Stout (1844-1930) in his role as Attorney-General. Walter Buller (1838-1906) had been involved in the dealings which, as several headlines stated, amounted to a ‘scandal.’ Acting on Stout’s advice, the Government passed the Owhaoko and Kaimanawa-Oruamatua Reinvestigation of Title Act 1886, which ‘returned the land to its pre-court status as native land and protected the extant leases – those of the Studholmes on Owhaoko and the Birches on Kaimanawa-Oruamatua.’ In establishing their station in 1868, the Birch brothers were the first European residents in this area, and they immediately constructed a cob house as their initial homestead. Maori Land Court evidence from Hiraka te Rango, son of Ngati Whitikaupeka rangatira Ihakara te Raro, stated that he was amongst those who assisted in constructing the homestead. Referencing Samuel Butler’s 1872 satire, the station became known as Erehwon. During William Birch’s lifetime this original spelling was upheld, which was ‘nowhere’ spelt backwards. The Birch family was from Pudlicote in Oxfordshire (central southern England), whereas cob construction is said to have been most typical amongst New Zealand settlers from south-west England. Therefore, a stronger motivation for using cob, or a cob-like mixture, seems to have been the lack of suitable timber in this high country area characterised by alpine vegetation such as tussock and bracken. Timber would have had to be carted from Hawke’s Bay up an arduous track, making it a comparatively expensive option to use for the entire building. The Birch brothers’ station was relatively isolated until the 1880s when the dray road from Hawke’s Bay reached it. Access options from the west increased in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century with the development of the North Island Main Trunk railway through Taihape. Initially the brothers seem to have shared the house. Because of these living arrangements the building was eventually expanded to 11 rooms, again in what is thought to be cob. While William and his wife Ethel did not have any children, Azim and Dora had several from the late 1870s onwards. However, the original station was divided in 1896 and the Birch brothers’ partnership was formally dissolved the following year. Apparently the brothers had a violent quarrel, which prompted a dice throwing competition to determine which part of the station each would operate. Azim won and retained the first homestead and associated farm, Oruamatua, while William, keeping the name Erehwon, developed his farm and its residence built around 1884. At the time it seems that William Caccia-Birch, adopted son of his uncle William Birch, was living at the station. Caccia-Birch was annoyed at Azim’s decision to keep the homestead portion, musing that: ‘No words or writing can express my feelings, so perhaps silence is golden. The relief of my dear Uncle Willie having got free from such a partner will I feel sure compensate us for our sentiment.’ William and Ethel seem to have been living at the cob homestead at the time, so had to vacate, which was done by the end of March 1897. The size of the original run is indicated by the fact that the main woolshed was five miles away from the homestead. When it was divided Azim had to build new facilities for the operation of Oruamatua. Therefore, in 1897 the stables, blacksmith’s workshop, and shed, close to the house were completed as well as a new woolshed with capacity for 2000 sheep, and staff quarters further away. At this time Mr Stoddart was the station’s manager, and he supervised the construction work undertaken by Hastings contractor, Mr Melville, and his labourers. Aside from his farming activities, Azim was also a prominent member of the local community. For instance, he was the Patea representative on the Hawke’s Bay County Council in the 1880s and 1890s, serving alongside the likes of Thomas Tanner (1830-1918) and Robert Donald Douglas McLean (1852-1929). He was also on the Patea Road Board in the 1880s. In the early twentieth century Azim was referred to as being of ‘South Kensington, and Oruamatua, New Zealand,’ although after the Erehwon split he is said to have predominately resided in England. Azim’s son William Reginald Birch (1881-1957) lived on site, managing the station, from 1903. When Oruamatua was sold in 1905, to Thomas Henry Lowry (1865-1944) and his brother-in-law Edward James Watt, it consisted of ‘4000 acres freehold, and 64,000 acres [of] leasehold [land], together with 32,000 sheep and 350 head of cattle…’. Earlier that year the land had been transferred to Azim, ending the almost 40 year old lease arrangement. Lowry was from a well-established Hawke’s Bay farming family who had the Okawa station from the 1850s. He was known as ‘one of New Zealand’s leading pastoralists.’ Furthermore, Lowry was described as ‘one of the most widely-known men in New Zealand through his love of sport, his position as a breeder of cattle and racehorses, and his many patriotic gifts….’ Watt was also from a wealthy and successful family of Hawke’s Bay landowners and horse breeders from their Longlands stud. The Lowrys are known to have visited Oruamatua and stayed in the homestead. One bedroom’s ceiling was specially lined with a thin tin because Mrs Lowry is said to have been worried that rats would be able to push their way through its calico lining while she slept. Lowry and Watt later subdivided and sold off parts of the station in 1920, at which time Oruamatua was described as having ‘a comfortable residence.’ The station was one of the largest in Rangitikei County at the time in terms of the numbers of sheep it supported. For example, there were 27,500 sheep and lambs at Oruamatua in 1914. The only other local station with comparable numbers was William John Birch and Son’s Erehwon station. By 1920 Oruamatua and Robert Batley’s estate at Moawhango had similar stock numbers, placing them in the county’s top 5. Lowry and Watt initially offered land to the Government for post-First World War soldier re-settlement, but the asking price was not met. Subsequently, 23,000 acres was divided into 9 farms for private sale. The Government had established a number of soldier settlements in the Rangitikei following the First World War. However, the resulting farmlets were predominantly dedicated to dairying, which could be a reason why the high country land, better suited to sheep farming, was not as desirable to them for their re-settlement programme. The subdivided section with the original homestead carried on the former station’s name and was purchased by Frederick Randall Cottrell in 1920. However, it seems that huge high country Rangitikei sheep stations were becoming a thing of the past by the mid-1920s. With a few exceptions, most properties in the district were like Oruamatua, having less than 5,000 sheep. This is reflective of a general trend in New Zealand in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, encouraged by government policy, to break up large stations and estates. The Cottrells have become a well-known Rangitikei farming family through their long association with Oruamatua. Frederick Cottrell and his family had a connection to Oruamatua prior to purchasing the Birch Homestead section, because Frederick had been the station manager there for several years. Frederick’s youngest son Derek Lyndsey Cottrell (1925-1992) followed as the next owner of Oruamatua. Known as Derry, he was also involved with local politics, being Erewhon Riding’s representative on the Rangitikei County Council in the mid-1970s and later a Rangitikei District councillor until his death. The family have continued to farm at Oruamatua through Derry’s son Mark. The farm’s 1860s cob homestead continued to be used by the Cottrell family until a brick residence was constructed closer to the Taihape-Napier Road in 1960. The Birch Homestead’s residence and outbuildings have been abandoned since then and in 2013 are in a dilapidated state as a result.

An 1888 description of the Birch Homestead’s surroundings is still applicable: ‘Messrs Birch’s [sic] homestead occupies a commanding view of the surrounding country for miles, and is situated on a lovely knoll, surrounded with trees…’ The original homestead area, featuring the house and its outbuildings as well as a timber stable and blacksmith’s workshop, is located away from the main road within what remains a large high country farm. The domestic buildings have a close perimeter fence designed to keep stock away from the buildings. Although referred to throughout the twentieth century as a clay or mud house, the Birch Homestead’s residence is probably constructed from cob. Mud or clay form this material’s main component, but straw and animal dung were also mixed in, creating a kind of concrete. It is unclear from current information whether the components of the material, or the construction method, were typical of other cob buildings. Other earth construction techniques used in New Zealand include pisé. However, that rammed earth technique does not seem to have been used for the house as there do not appear to be pebbles in its wall and or evidence of the construction moulding required for this method. Early photographs of house’s site indicate it was created by excavating into the hillside behind. This spoil was then probably used in the building’s construction. Originally the house’s exterior cob walls were plastered. However, board and battens, and weatherboards, were added to the exterior at some stage in or prior to 1897, remnants of which are on the north and southern sections respectively. The plaster and cladding is damaged in most areas, exposing the cob beneath. There are currently (2013) no North Island cob residences registered as historic places. Settler handbooks promoted this relatively easy and cheap construction method for early buildings. As such, cob buildings were once reasonably common in New Plymouth settlement’s beginnings, but the majority of remaining examples are located in the Nelson, Marlborough, and Canterbury regions. The only North Island example on the Register is Cob Dairy – ‘Ferngrove’ (Category 2 historic place, Register no. 2715) in Taranaki. The main building of the Birch Homestead therefore seems unique in its Hawke’s Bay/Rangitikei context, very rare in the North Island, and it is also significant as the earliest remaining building locally. The house consists of three sections, containing 10 rooms. Therefore, it is larger than many of New Zealand’s other remaining earth construction houses which, with the exception of places such as Russell’s Pompallier (pise construction; Register no. 4) and Broadgreen (cob construction; Register no. 252) in Nelson, are generally small cottages with only a few rooms. The main section is a typical English Colonial style double box cottage whose form is comparable to another homestead near Nelson, Cob House (circa 1863; Register no. 1633). Like most walls of the Birch Homestead’s house, this building’s ground level exterior walls are cob. It would initially have been divided into four rooms off from a central passage, and has a verandah around several sides. However, a key difference is that the Nelson Cob House has remained a residence, while its Rangitikei counterpart is ramshackle because of a corresponding lack of purpose and maintenance. Reportedly rodent damage was evident within a few years of the former Birch house’s abandonment in 1960. In particular though, part of the rear cob wall, and southern section’s east exterior and interior wall have collapsed, seemingly from tree and chimney fall. The original extent of the residence has not been confirmed, although the main section appears to have been constructed last, sometime between 1878 and 1897. The Birch brothers would most likely have started with one initial section and then expanded the building further, so at least they had some basic shelter to start off with. This was common practice in contemporary residences, with additions created as resources allowed. Therefore, it is probable that the smallest part, the middle section, dates to 1868, with the southern section being added within a decade. Another representative feature of the house is its verandah. The house’s main, or northern, section has a timber constructed verandah wrapped around its north and west sides. This connects to the east side of the building and continues along that length. There are some remnants of decorative timber scalloping along the front of the middle section. This is also present on the eastern-most outbuilding. The roofline of the house clearly delineates its sequential construction. The main section has a hipped roof with the base of the collapsed brick chimney emerging at the west of the ridge. The middle part has a crossways gable, while the longer, southern section has a hipped roof. Although the roof is clad in corrugated iron, timber roofing shingles are visible beneath. 12-light double hung sash windows are used throughout the building. Some have panes missing, and the southern section is missing several upper sashes. The main entrance is on the north side of the northern section at the head of the arterial passage. The main section’s passage is atypical of double box cottages because it is not centrally positioned, being specifically aligned to the existing passageways of the middle and southern parts of the building. The respective sections are unified by roofing, which mean the areas between form secondary transverse passage ways. As a result a formerly exterior north wall window of the middle section was enclosed. Each section also has its own external entrance. There is also only external access to the room on the house’s southeast corner. In the main section the interior walls are timber and appear to be in reasonable condition, as are the timber roof rafters and linings. Some interior fittings remain, such as the fireplace surrounds and cabinetry. The interior doors have been removed and could be reinstated if the building is made water-tight again. While the main section’s living rooms had modern linings installed in the early to mid-twentieth century, in the 1960s it was reported that all the other rooms retained their original calico ceiling linings. It appears that some of this material has survived in the main section’s hallway and living areas. The house’s main section appears to have included family and entertaining rooms, a bedroom and a bathroom. The middle section may have contained a western bedroom, whose south cob internal wall has collapsed. This wall used to contain a fireplace flanked by wardrobe joinery. The eastern room of the middle section appears to have been a dining area as it connects directly to the south section’s kitchen areas. A cooking range remains in the east room of the south section. A timber walled extension encloses the southwest corner, and appears to have been used as a laundry. Only a few metres away from the southern end of the house are a series of three simple gabled outbuildings, which ascend in size from east to west and appear in the 1897 photographs. These are also in a state of disrepair. From east to west they seem to be an outhouse, shed, and a two roomed auxiliary accommodation building. This last building has a longitudinal gable, front verandah, a central chimney on its back wall, and front and rear access. These timber framed buildings are mostly clad in timber but corrugated iron has also been used. About 100 metres away, to the west of the house’s knoll are the remaining homestead buildings, its farm buildings. The timber framed and clad stable, and blacksmith’s workshop, and a shed were constructed by Mr Melville in 1897. As is typical of these types of buildings, they appear to have been repaired when necessary with easily accessible materials, such as recycled timbers and corrugated iron. The blacksmith’s workshop and implement shed adjoin each other, and are gable roofed buildings. The east part is the shed which is fully enclosed and has a loft section. This building is a storage space and has been maintained as such. There is evidence that the flashings were recently renewed. The adjoining single storey part has an open front on its northern side, facing into the courtyard-like grassed area defined by the right-angle location of the stables. The stables is also a gable roofed, timber framed and clad structure, with corrugated iron roof. This material has also been used for sections of the wall cladding, as well as on the shed. This building could originally house 10 horses, and has Dutch doors although only one complete set remains. Because these doors would have closed-in the building, the east side also features louvered openings for each stall, in order to provide ventilation and some light.

Public NZAA Number

T21/1335

Completion Date

26th July 2013

Report Written By

Astwood, K

Information Sources

Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives (AJHR)

Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives

Wises Post Office Directories

Wises Post Office Directories

Maori Land Court

Maori Land Court

Newton, 1969

P. Newton, Big Country of the North Island, A. H. & A. W. Reed, Wellington, 1969

Salmond, 1986

Jeremy Salmond, Old New Zealand Houses 1800-1940, Auckland, 1986, Reed Methuen

Cochran, 1997

C. Cochran, ‘Oruamatua, Oruamatua Marae, Moawhango,’ Conservation Report, Oruamatua Marae Trust, 1997

Laurenson, 1979

S. G. Laurenson, Rangitikei: the day of striding out, Palmerston North, Dunmore Press, 1979

Riseborough, 2006

Hazel Riseborough, Ngamatea: The land and the people, Auckland, Auckland University Press, 2006

Report Written By

A fully referenced registration report is available from the Central Region of the New Zealand Historic Places Trust. Please note that entry on the New Zealand Heritage List/Rarangi Korero identifies only the heritage values of the property concerned, and should not be construed as advice on the state of the property, or as a comment of its soundness or safety, including in regard to earthquake risk, safety in the event of fire, or insanitary conditions.

Current Usages

Uses: Accommodation

Specific Usage: House

Uses: Agriculture

Specific Usage: Barn

Uses: Agriculture

Specific Usage: Shed

Former Usages

General Usage:: Accommodation

Specific Usage: House

General Usage:: Accommodation

Specific Usage: Shed/store - Residential out-building

General Usage:: Accommodation

Specific Usage: Stables - Residential out-building

General Usage:: Agriculture

Specific Usage: Barn

General Usage:: Agriculture

Specific Usage: Stables

General Usage:: Trade

Specific Usage: Blacksmith

Themes

Web Links

Stay up to date with Heritage this month