When Choie Sew Hoy and his son Choie Kum Poy went to Nokomai in 1894, their efforts led to a gold mining revival that gave renewed hope to large numbers of miners who returned to the district. Sew Hoy’s company hired up to 40 men, who installed and worked a hydraulic sluicing and elevator plant. Sew Hoy proposed to bring water by first one and then two new long water races, to be constructed by Chinese and European workmen through rugged terrain using inverted siphons instead of flumes. The Nokomai Hydraulic Sluicing Company was to work the Nokomai Valley until 1943, an unusually long-lasting sluicing claim in this boom and bust industry.

Choie Sew Hoy is a significant figure in New Zealand history. He was responsible for two major gold mining revivals, one in Otago and the other at Nokomai in Otago/Southland, and was involved in a wide range of mining activities. Choie Sew Hoy was a key figure in gold mining in New Zealand, and also had an important role in introducing a new type of steam dredge. The dredge opened up ground for a new system of mining, sparking an economic revival in Otago at the turn of the century. Historian James Ng could think of no other nineteenth century Chinese individual who gained as much wealth from gold mining and only one other (Chew Chong in Taranaki) who gained as much wealth or standing in New Zealand.

Sew Hoy’s workings at Nokomai and the associated race system represent the technologies associated with hydraulic sluicing. Hydraulic sluicing leaves a particular pattern of archaeological evidence – a system of water races, water storage features, and gold workings, as well residential areas associated with working the claims. Ground and hydraulic sluicing took over from the cradle and pan. Hydraulic sluicing required more head (water pressure) – large races were built to bring water to the working face. The working face of the claim was worked with a high impact water jet directed from a moveable nozzle. Sew Hoy’s Workings and Water Race System provides an outstanding example of a race system and workings associated with hydraulic sluicing in the late nineteenth, early twentieth century and later again in the 1980s. Of particular note are the Roaring Lion and Diggers Creek water races.

In 2017, Sew Hoy’s Nokomai Workings and Water System remain archaeological features in the dramatic landscape of the Nokomai and Upper Nevis Valleys. Part of the Roaring Lion Race is accessible via a walking and biking trail.

Location

List Entry Information

Overview

Detailed List Entry

Status

Listed

List Entry Status

Historic Place Category 1

Access

Private/No Public Access

List Number

9291

Date Entered

16th May 2019

Date of Effect

5th June 2019

City/District Council

Southland District,Central Otago District

Region

Southland Region

Extent of List Entry

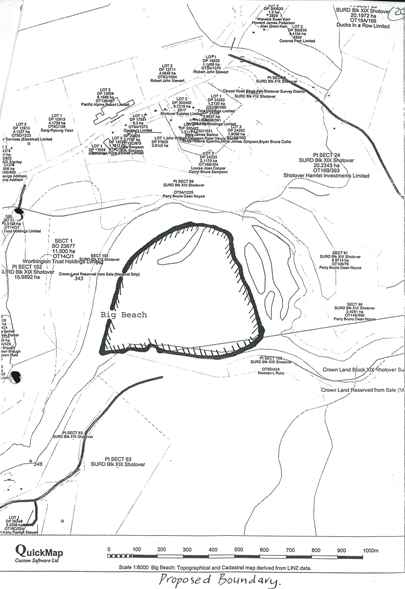

Extent includes the land described as Lot 3 DP 309692 (RT 38175), Water Race Block III Kingston SD, Water Race Block II Nokomai SD, Water Race Block III Nokomai SD, Water Race Block IV Nokomai SD and parts of the land described as Sec 9 and Pt Sec 10 Blk III Kingston SD (RT SL8C/337), Water Race Blk III Kingston SD, Sec 11 Blk II Nokomai SD (RT SL45/83), Sec 12 Blk II Nokomai SD (RT SLB3/1372), Secs 16-18 Blk II Nokomai SD (RT SLB3/1408), Water Race Blk II Nokomai SD, Secs 6-8 Blk III Kingston SD (RT 763821), Sec 20 Blk VII Nokomai SD (RT SL7B/540), Sec 22 Blk VII Nokomai SD (RT SL7B/463), Water Race Blk VII Nokomai SD, Crown Land Blk VIII Nokomai SD, Sec 1 Blk VIII Nokomai SD (RT SL10B/121), Crown Land Blk I Rockyside SD, Lot 1 DP 309692 (RT 38174), Lot 2 DP 309692 (RT 38175), Pt RUN 323B (RT SL201/179), RUN 625 (RT SLA2/1299), Secs 1-2 SO 438637 (RT 549720), Secs 4-5 SO 438637, Legal Road, Legal River, Southland Land District, and the archaeological sites associated with Sew Hoy’s Gold Workings and Water Race System thereon. (Refer to map in Appendix 1 of the List entry report for further information).

Legal description

Lots 2-3 DP 309692 (RT 38175), Water Race Block III Kingston SD, Water Race Block II Nokomai SD, Water Race Block III Nokomai SD, Water Race Block IV Nokomai SD, Sec 9 and Pt Sec 10 Blk III Kingston SD (RT SL8C/337), Water Race Blk III Kingston SD, Sec 11 Blk II Nokomai SD (RT SL45/83), Sec 12 Blk II Nokomai SD (RT SLB3/1372), Secs 16-18 Blk II Nokomai SD (RT SLB3/1408), Water Race Blk II Nokomai SD, Secs 6-8 Blk III Kingston SD (RT 763821), Sec 20 Blk VII Nokomai SD (RT SL7B/540), Sec 22 Blk VII Nokomai SD (RT SL7B/463), Water Race Blk VII Nokomai SD, Crown Land Blk VIII Nokomai SD, Sec 1 Blk VIII Nokomai SD (RT SL10B/121), Crown Land Blk I Rockyside SD, Lot 1 DP 309692 (RT 38174), Pt RUN 323B (RT SL201/179), RUN 625 (RT SLA2/1299), Secs 1-2 SO 438637 (RT 549720), Secs 4-5 SO 438637, Legal Road, Legal River, Southland Land District

Location Description

Additional Location Information The Diggers Creek Race runs from Diggers or Starlight Creek on the western slopes of the Hector Range, before dropping over a saddle into the Nokomai Valley. The Roaring Lion Race intake is at Roaring Lion Creek on the western slopes of Garvie Mountains before it crosses to the eastern slopes of the Slate Range. Both races terminate above the Nokomai Valley close to Nokomai Station, providing water to the workings below. The gold workings are located up the Nokomai Valley from upper Donkey Flat in the north to Nokomai Station in the south, centred on the tributaries of the Nokomai River.

Status

Listed

List Entry Status

Historic Place Category 1

Access

Private/No Public Access

List Number

9291

Date Entered

16th May 2019

Date of Effect

5th June 2019

City/District Council

Southland District,Central Otago District

Region

Southland Region

Extent of List Entry

Extent includes the land described as Lot 3 DP 309692 (RT 38175), Water Race Block III Kingston SD, Water Race Block II Nokomai SD, Water Race Block III Nokomai SD, Water Race Block IV Nokomai SD and parts of the land described as Sec 9 and Pt Sec 10 Blk III Kingston SD (RT SL8C/337), Water Race Blk III Kingston SD, Sec 11 Blk II Nokomai SD (RT SL45/83), Sec 12 Blk II Nokomai SD (RT SLB3/1372), Secs 16-18 Blk II Nokomai SD (RT SLB3/1408), Water Race Blk II Nokomai SD, Secs 6-8 Blk III Kingston SD (RT 763821), Sec 20 Blk VII Nokomai SD (RT SL7B/540), Sec 22 Blk VII Nokomai SD (RT SL7B/463), Water Race Blk VII Nokomai SD, Crown Land Blk VIII Nokomai SD, Sec 1 Blk VIII Nokomai SD (RT SL10B/121), Crown Land Blk I Rockyside SD, Lot 1 DP 309692 (RT 38174), Lot 2 DP 309692 (RT 38175), Pt RUN 323B (RT SL201/179), RUN 625 (RT SLA2/1299), Secs 1-2 SO 438637 (RT 549720), Secs 4-5 SO 438637, Legal Road, Legal River, Southland Land District, and the archaeological sites associated with Sew Hoy’s Gold Workings and Water Race System thereon. (Refer to map in Appendix 1 of the List entry report for further information).

Legal description

Lots 2-3 DP 309692 (RT 38175), Water Race Block III Kingston SD, Water Race Block II Nokomai SD, Water Race Block III Nokomai SD, Water Race Block IV Nokomai SD, Sec 9 and Pt Sec 10 Blk III Kingston SD (RT SL8C/337), Water Race Blk III Kingston SD, Sec 11 Blk II Nokomai SD (RT SL45/83), Sec 12 Blk II Nokomai SD (RT SLB3/1372), Secs 16-18 Blk II Nokomai SD (RT SLB3/1408), Water Race Blk II Nokomai SD, Secs 6-8 Blk III Kingston SD (RT 763821), Sec 20 Blk VII Nokomai SD (RT SL7B/540), Sec 22 Blk VII Nokomai SD (RT SL7B/463), Water Race Blk VII Nokomai SD, Crown Land Blk VIII Nokomai SD, Sec 1 Blk VIII Nokomai SD (RT SL10B/121), Crown Land Blk I Rockyside SD, Lot 1 DP 309692 (RT 38174), Pt RUN 323B (RT SL201/179), RUN 625 (RT SLA2/1299), Secs 1-2 SO 438637 (RT 549720), Secs 4-5 SO 438637, Legal Road, Legal River, Southland Land District

Location Description

Additional Location Information The Diggers Creek Race runs from Diggers or Starlight Creek on the western slopes of the Hector Range, before dropping over a saddle into the Nokomai Valley. The Roaring Lion Race intake is at Roaring Lion Creek on the western slopes of Garvie Mountains before it crosses to the eastern slopes of the Slate Range. Both races terminate above the Nokomai Valley close to Nokomai Station, providing water to the workings below. The gold workings are located up the Nokomai Valley from upper Donkey Flat in the north to Nokomai Station in the south, centred on the tributaries of the Nokomai River.

Cultural Significance

Cultural Significance or Value Sew Hoy’s Gold Workings and Water System has a clear association with the early New Zealand Chinese miners in Otago (and Southland), as well as the outstandingly significant Choie Sew Hoy and his family. Sew Hoy employed Chinese miners and workers, creating a long-standing Chinese community in this isolated area. The cultural remains provide insight into the life and work of Chinese miners in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Nokomai and Sew Hoy feature in James Ng’s landmark publication Windows on a Chinese Past. This significant association gives the place cultural significance.

Historic Significance

Sew Hoy’s Gold Mining and Water Race System represents the significant history of Chinese gold mining in Otago and more widely in New Zealand. It particularly represents the lives of Chinese miners in isolated fields, such as Nokomai. It also gives insight into the history and role of Choie Sew Hoy, an outstanding figure in the history of New Zealand gold mining, particularly in Otago, and of the important history of the Chinese community in Otago.

Physical Significance

Aesthetic Significance or Value Sew Hoy’s Gold Workings and Water Race System snaking across the tops of the Garvie Mountains, the Slate Range and the Hector Mountains, subject to the heat of summer and the blistering cold of the south’s harsh winters gives a powerful insight into the work and lives of the miners who braved these extreme conditions. Walking the race, knowing that each step marks the hard labour of hand building the races and mining the gold is a sobering reminder of what it was like for miners in this isolated goldfield. These elements give the place special aesthetic significance. Archaeological Significance or Value Sew Hoy’s Gold Workings and Water System has archaeological significance showing the integrated mining systems associated with hydraulic sluicing, and the associated settlement remains. The alluvial mining systems with water races, reservoirs, tailings, sluicing ponds and faces and tail races show the technologies used from the 1860s through to the 1940s. These systems are relatively undisturbed due to the isolation of Nokomai. The huts have the potential to provide archaeological information about the lives of miners, particularly Chinese miners, in this isolated environment. Technological Significance or Value The Sew Hoy’s Gold Workings and Water Systems have technological significance, illustrating the techniques used to build the race, calculating the fall over long distances and integrate the race system with the sluicing faces.

Detail Of Assessed Criteria

(a) The extent to which the place reflects important or representative aspects of New Zealand history Sew Hoy's hydraulic sluicing operation is associated with the nineteenth century gold rushes in Otago and Southland, which were pivotal to the economic development of New Zealand. Sew Hoy’s story is also associated with Chinese immigration and the significant role and presence of the Chinese in New Zealand. Sew Hoy's success proved that they could successfully enter the European commercial world. Along with the Sew Hoy’s Big Beach Historic Area (List No. 7545), Sew Hoy’s association with Nokomai recognises Sew Hoy’s significant role in gold mining and his business standing in Otago’s Chinese and European communities. (b) The association of the place with events, persons, or ideas of importance in New Zealand history Sew Hoy’s Gold Workings and Water System is associated with gold mining, specifically hydraulic sluicing in Otago and Southland in the nineteenth century through into the mid-twentieth century. Such mining changed the face of Otago forever, and is of great importance to New Zealand’s history. The workings are also associated with Sew Hoy and his family, pioneering miners and business people in New Zealand’s Chinese community, and innovators in gold dredging. (c) The potential of the place to provide knowledge of New Zealand history The physical remains of Sew Hoy’s Nokomai Workings and Water System provide an example of an intact integrated system of workings, and have the potential to provide important insights into the technology of hydraulic sluicing in the Nokomai Valley, and also more widely in Otago. The hut remains have the potential to provide information about the lives of Chiners miners. (e) The community association with, or public esteem for the place The community has been involved with the restoration of the sod hut on the Roaring Lion Race. Community support is evident through the participation of volunteers, the support of the Department of Conservation, and of the 1990 Commission. (f) The potential of the place for public education Part of the Roaring Lion Race is accessible to the public via a walking track and provides visitors with a powerful vision of the scale and techniques for building a water race. There are plans for on-site interpretation that will add to the impact and understanding of the place. (g) The technical accomplishment, value, or design of the place Building water races shows a great deal of technical accomplishment. The Roaring Lion Race had to traverse extremely steep and rugged country as well as cross the divide between the Garvie Mountains and the Slate Range, all while keeping the appropriate level of fall for the race to function. The Diggers Creek Race also traversed steep country and crosses from the west to east faces of the Slate Range. Integrating these races into the mining system was a complex matter for the builders of the races. (k) The extent to which the place forms part of a wider historical and cultural area Sew Hoy’s Gold Workings and Water System is a historic mining landscape in its own right, as well as being part of the wider mining and cultural landscape of the Upper Nevis and Nokomai Valleys. Summary of Significance or Values Sew Hoy’s Nokomai Workings and Water System has outstanding historical significance. It is strongly associated with pioneering Chinese businessman Choie Sew Hoy and his family and was one of the longest running and most successful hydraulic sluicing claims in Otago and Southland. It provides insight into an integrated system of workings and water races in an isolated and rugged area of Otago and Southland.

Construction Details

Description

First gold rush to Nokomai

Finish Year

1862

Type

Other

Description

Diggers Creek race already in existence

Finish Year

1888

Type

Other

Description

Sew Hoy mining operations begin

Finish Year

1894

Type

Other

Description

Golden Lion Sluicing Company cut their race from Roaring Lion Creek

Finish Year

1898

Type

Other

Description

Sew Hoys complete installation of two hydraulic sluicing plants at Nokomai

Finish Year

1898

Type

Addition

Description

Sew Hoy mining operations cease

Finish Year

1943

Type

Other

Description

L&M Mining Limited reopened some Nokomai mining sites

Finish Year

1989

Type

Other

Construction Materials

Huts: Timber, corrugated iron, sod, stone, iron

Ngāi Tahu have a long association with Central Otago and Southland and its rivers, with values of kaitiakitanga, mauri, wāhi tapu, wāhi taoka and traditional ara or trails. Trails ran up Te Papapuni (the Nevis River) and through Nokomai. Māori trails in the South Island high country provided significant social and economic links. These trails tended to follow valleys. The importance of the rivers to iwi is illustrated by their inclusion in the Otago Regional Plan – Water 2004. Tūtūrau chief Reko (c.1803-1868) led pastoralist Nathanael Chalmers from the Mataura River to the Nokomai and into the Nevis River in 1853, the first European to see the remote valley. Reko, who had lived near Kaiapoi, and who had shifted close to Tūtūrau in Southland, had a detailed knowledge of the interior, drawing maps for visitors. He became a well-known guide. The Otago Gold Rushes Europeans soon found their own value in the hills and rivers. The Otago gold rushes followed on the heels of the Californian rushes of the late 1840s and early 1850s, and the Australian rushes of the mid to late 1850s. Many miners followed the gold finds around the Pacific, bringing the knowledge, technology, and experience of previous fields. Such is true of some of both the European and Chinese miners. There had been reports of the presence of gold in the Otago Province throughout the 1850s, which met with official suspicion and discouragement to preserve order. Gabriel Read’s 1861 discovery near what is now Lawrence led to a surge of prospectors who followed the new discoveries around the Otago and into northern Southland. Prospectors explored to Nokomai, near the southern tip of Lake Wakatipu, and the Nevis River. Following in their wake were the Chinese miners, who arrived in the mid-1860s. The Chinese Miners The gold seekers in Otago included around 10,000 Chinese men, and despite their relatively late arrival, they constituted ‘one of the largest and certainly the most conspicuous ethnic group on the goldfields.’ The majority of Chinese people who came to New Zealand in the nineteenth century were from the clans of Poon Yue, Nanhai, Zang Sheng and Si Yap. Their aim was to earn £100 as fast as possible to return to China with enough money to buy a plot of land. Chinese miners were familiar with alluvial mining, and also the principles of hydraulic engineering used for irrigation in China. Some also had mining experience in other goldfields. Chinese miners tended to move together, and live separately from Europeans because of the anti-Chinese feeling rife among European miners. Many Europeans opposed Chinese immigration. Opposition came to a head in 1881 when a poll tax was introduced along with other racist legislation. Despite the racism, some Chinese miners managed to make a successful living and others made an important contribution to the economy of Otago. Choie Sew Hoy and his associates were foremost among these. Chinese miners faced open racism on the goldfields and legalised discrimination through the 1881 Chinese Immigrants Act, which imposed the £10 poll tax (equivalent to nearly $1700 in today’s currency) on Chinese migrants, and restricted the number who could come to New Zealand. In 1896, the tax was increased to £100 ($19,000). Anti-Chinese associations were formed to oppose Chinese immigration. The poll tax was waived from 1934, but not repealed until 1944. In 2002, the New Zealand government officially apologised to the Chinese community for the injustice of the tax. Choie Sew Hoy (c.1838-1901) Choie Sew Hoy was a Dunedin merchant and importer, businessman and investor in gold mining operations, as well as a public benefactor. He was born in Sha Kong, 20 kilometres north of Guangzhou in the Upper Panyu District. As a young man, Choie Sew Hoy joined other Cantonese gold seekers, going first to California, and then to Victoria. Historian James Ng suggests that Choie Sew Hoy came to New Zealand in 1868, and set himself up as a merchant in Dunedin. Sew Hoy had become prominent by 1871 and encouraged Panyu Cantonese migration to Otago in the early 1870s. Sew Hoy was one of several Chinese merchants who had stores around the Stafford Street area in Dunedin. Sew Hoy was naturalised in 1873. He married Young Soy May and they had a daughter and two sons. When he was about 50, he formed a de facto relationship with Eliza Prescott, with whom he had had two children. On his death in 1901, Sew Hoy was buried in the Anglican sector of the Dunedin Southern Cemetery but was disinterred by the Cheong Shing Tong (the benevolent society of Panyu and Hua migrants, run from Sew Hoy’s store and led by Sew Hoy and later his son) the following year to be taken back to China. Sew Hoy was admired by the Chinese community for his public spirit and was honoured with a special rimu coffin as a mark of this respect. Unfortunately, the ship returning his and the remains of 498 other Chinese men who had died in New Zealand to China, the SS Ventnor, struck a rock and sank off Hokianga, and only ten coffins floated ashore. Sew Hoy advised, outfitted, provisioned and otherwise helped Chinese gold seekers. He also supplied Chinese stores in the goldfields. He and son Choie Kum Poy used the credit ticket system to bring out kinsfolk and friends of the family to work their gold dredges and gold-sluicing claims. In exchange for the fare, the emigrant agreed to work out the debt on arrival. Choie Kum Poy brought out his last group of six workers in 1923. Choie Sew Hoy was responsible for two major mining revivals, one in Otago and the other at Nokomai in northern Southland. He had mining interests throughout Otago including at Mt Ida, Skippers, Kyeburn and Big Beach. Choie Sew Hoy was the principal person involved in introducing a new type of steam dredge that opened up ground for a new system of mining, prompting the creation of a large dredging fleet, and sparking an economic revival in Otago at the turn of the century. Historian James Ng could think of no other nineteenth century Chinese who gained as much wealth from gold mining and only one other (Chew Chong in Taranaki) who gained as much wealth or standing in New Zealand. The Sew Hoys at Nokomai had an unusual permanency and stability. While other alluvial mining companies came and went, the Sew Hoys either headed or were close to the head of the list of successful alluvial miners for 50 years. Only major companies at Round Hill (in Southland) and Gabriel’s Gully had anything like a similar record. The Nokomai Hydraulic Sluicing Company headed all others in gold returns for nine years. From 1919 and especially after 1923 the company’s gold return diminished. In 1926, the company was restructured as the Nokomai Sluicing Company, and sluicing was shifted from the higher ground (Paddys Alley and Victoria Gully) to lower flats at Nokomai. Before restructuring the original company (1898-1926) had won 55,991oz of gold and paid £54,683 in dividends. According to James Ng, Choie Sew Hoy decisively proved that the early New Zealand-Chinese had the capacity for large-scale mining projects and that the Chinese could successfully enter the European commercial world. His pioneer role in the development of gold-dredging was recognised in his time. Ng argues that Sew Hoy was one of ‘Otago-Southland’s most enterprising, innovative and important gold miners. Because he was prominent in both gold-dredging and sluicing, and because he led two mining revivals, I consider him to have been the most important figure in the higher technical and capital input phase of Otago-Southland gold mining last century.’ In addition, Ng considers that ‘despite the prejudice and discrimination, the early New Zealand-Chinese produced two pioneers of remarkable standing in their adopted community: Choie Sew Hoy in gold-dredging and Chew Chong in butter manufacture.’ Nokomai Valley: Pastoralism and Gold Nokomai was divided into pastoral runs in the late 1850s, the Nokomai Flats first occupied by Donald Angus Cameron, who named the valley Glenfalloch (Hidden Valley). Cameron lived on the station until his death in 1918, a period of occupation of 59 years. Glenfalloch remained in the hands of the Cameron family until 1950, when it was bought by Francis Hore, who renamed it Nokomai, and extended the boundaries of the station. Gold was discovered in Moa Creek (later known as Victoria Gully) at Nokomai in 1862. Miner James Lamb reported that there was a large area of auriferous land bordering on Nokomai and extending over the dividing range to the Nevis and onto the Kawarau River. An area of 281,600 acres was formally designated as the Nokomai Gold Field. The rush quickly subsided, although there were two minor rushes the following decade. Miners worked the spurs of the ridges and the terraces. Nokomai township was established on the valley floor. At its greatest extent around 1873, the town had three hotels, a shop, stable and smithy, the school and a few scattered huts. By 1874, only 150 people lived in the area, 120 of whom were Chinese. By 1886, the township had only one dilapidated building acting as a store and hotel. After the West Coast rushes the Nokomai’s population dwindled. There was a brief revival in the mid-1880s, but by 1887, there were only 20 Chinese and 7 Europeans working. The flats were virtually abandoned around 1890. Choie Sew Hoy and Choie Kum Poy were to change all of this. With the advent of the Sew Hoy’s hydraulic excavators, mining continued steadily until about 1940, a long time for an Otago gold field. Sew Hoy’s Nokomai Hydraulic Sluicing Operations Sew Hoy’s Nokomai sluicing company has a special place in Otago’s mining history. Archaeologist Jill Hamel writes that the Sew Hoy’s Nokomai operation was one of the longest running and most prosperous mining ventures in Otago and Southland. When Choie Sew Hoy and his son went to Nokomai in 1894, their efforts led to a mining revival that encouraged large numbers of miners to return to the district with renewed hopes. Sew Hoy and his two sons Kum Yok and Kum Poy had been looking for other mining opportunities as early as 1893. They chose hydraulic sluicing and elevating at Nokomai and took up claims of 60 acres of high flats in the upper valley of the Nokomai River. They hired up to 40 men and installed a hydraulic sluicing and elevator plant. At Nokomai, Sew Hoy proposed to bring water by first one and then two new long water races, to be constructed by workmen through rugged terrain using inverted siphons instead of flumes. Sew Hoy’s workforce included both Chinese and Europeans. In 1894, two special claims over 120 acres were granted to Choie Sew Hoy and Kum Poy. The gold bearing deposits were below the level of the water table and required hydraulic elevators to retrieve the gold, a method used also at St Bathans and Blue Spur (near Lawrence). The Nokomai venture was working by December 1894, and was known as the ‘Sew Hoy Nokomai claim.’ Sew Hoy’s sluicing operation was one of the few non-dredging operations that attracted notice and technical praise during the late nineteenth-century dredging boom. In 1896, Sew Hoy’s Nokomai company employed 30 men, of whom 12 were Europeans. In 1897, Kum Yok returned to China, and Choie Sew Hoy and Kum Poy carried on the company. The Sew Hoys still had insufficient water and brought down another race from Donkey Flat that carried 24 heads of water. This was, according to archaeologist Jill Hamel, the major race using the Nokomai River. The Mines Department records three major races built by the Sew Hoys to Nokomai Flat, but only the one from Donkey Flat was clearly identified. The big race from Fosters Creek and Diggers Creek at the foot of the Hector Range already existed in 1888, and in 1894, the Sew Hoys either widened the old race or built a parallel one. By 1897, the Sew Hoy’s Nokomai Hydraulic Gold Mining Company had a claim of 128 acres and had constructed ten kilometres of water races, giving a total of 20 miles to which the company had rights. One race included 2 siphons of 3,400 and 720 feet [1036 m and 200 metres] respectively, made of pipes 18.5 inches [47 centimetres] in diameter, carrying 15-20 heads of water, and delivering 550 feet of pressure to the elevators. There were two sets of elevators working with 2050 feet [624 metres] of main line steel pipes and 1335 feet [407 metres] of service pipes for elevating and sluicing the drift. A Pelton wheel drove a three horsepower motor for the dynamo which provided electric light. The elevators were working down into 45 feet [14 metres] of gravels with no large boulders and using 11 heads of water elevated the wash 65 feet [20 metres]. Even with the race building, one month each year was lost from lack of water. The whole enterprise cost £15,200 pounds and employed 12 Chinese and 8 Europeans, as well as the 40 men employed to cut another water race. In 1898, the company completed the installation of two hydraulic sluicing and elevating plants and completed the first two water races of 42 and 34 kilometres respectively. They were also constructing their third and fourth water races and were employing some 20 men on sluicing and another 20 men on races. The Otago Witness commented ‘It is not saying too much that at the time no private individuals other than [Sew Hoy and Kum Poy] could have been found in New Zealand adventurous enough to invest a sum of £15,000 in this undertaking….’ Father and son floated the Nokomai Hydraulic Sluicing Company in 1898, issuing 2,400 shares at £10 each. Sew Hoy and Kum Poy became the biggest shareholders, each holding 850 shares, and they respectively became the company’s director and secretary. The share list included well-known Otago people, several who had been shareholders in both the Shotover Big Beach Gold Mining Company and the Sew Hoy Big Beach Gold Mining Company. In 1898, the sluicing returns of the Company were 100oz to 200oz of gold a month. By 1898, Sew Hoy’s Nokomai sluicing claim was a ‘marvellously rich sluicing claim [with] splendid water rights and capital plant.’ It yielded £7,000 for three months’ work. The key to the success of the venture was its long, well-engineered water races that ran from the Nevis River to Nokomai. The Roaring Lion Race – Expansion of Mining In 1899, the Golden Lion Sluicing Company cut an over 40-kilometre long, 25 head water race from the Roaring Lion Creek to the Nokomai Valley. The race took 3 years to complete, cost £11,000 and supplied around 600 feet of head. The race started at the headwaters of the Roaring Lion Creek and finished at the sluicings opposite the Nokomai homestead. The Sew Hoys bought the Golden Lion Sluicing Company and the race in 1906 and used it to work all three of their claims. To work the No.3 claim in Victoria Gully the water from the race was transferred into the race system from Donkey Flat, across the Nokomai River in a big siphon above the confluence with Bullock Head Creek and down the south-east side of the valley to Victoria Gully. The Sew Hoys built a dam at Donkey Flat in 1903. Hamel described it as having breast work of 40 feet [12 metres], backing water up to cover 17.75 acres [7 hectares]. Three years later it was described as 26 feet high [8 metres], to be raised another 10 feet [3 metres] to add another eight acres [3.2 hectares] of water. The increased water supply from this dam, and the Roaring Lion Race may have allowed the Sew Hoys to increase their workforce from about 15 to 30 men and then to 60 men by 1908. From 1911 to 1914 the Nokomai Hydraulic Sluicing Company headed all other registered alluvial gold mining companies in New Zealand and paid steady dividends. During 1914 to 1918 the No. 3 plant on the old Lion Sluicing claim in Victoria Gully was moved down the creek and back into Victoria Gully where the No. 2 elevator was still working. The No.1 elevator was closed down about 1914. The Sew Hoys worked steadily and prosperously in Victoria Gully until 1927. In 1927, they shifted out onto the Nokomai Flats to build a large hydraulic elevator and extended their water races. Lengths of pipe were laid, extending the No.2 water race across Victoria Gully, and further extending it around a mile (1.6 kilometres) to the penstock overlooking the claim . The penstock consisted of 800 metres of pipes delivering 25 heads of water with a pressure of 400 feet. The No.1 race delivered water from the Roaring Lion Race and the Diggers Creek Race coming in over Nokomai Saddle. A branch race of 5.6 kilometres carried the water to a penstock 480 metres long at a pressure of 560 feet. The paddocks which these water systems were gouging out were on the west side of the valley, up to 82 feet [25 metres] deep and one of them 140 by 40 metres. The paddocks were regularly backfilled when adjacent ground was worked. Jill Hamel considers that it ‘is difficult to know whether these paddocks are still visible features of the landscape.’ In 1932, the company was restructured into the Nokomai Gold Mining Company, with the assistance of mining associate James Fletcher (1886-1974), in order to use the technologically new dragline excavator on new claims at Nokomai. Kum Poy (1867-1942), who had taken over his father’s mantle (and had adopted Sew Hoy as his English surname after his father’s death), was described by Fletcher as ‘a remarkable man whose word was his bond and even in adversity he never accepted defeat.’ The older company had not done well, due to the poor auriferous ground, and it was hoped the new method would reverse the decline. The excavator failed when it struck a very hard layer, and the company closed down in 1943, after a flood and Kum Poy’s death the previous year. After Kum Poy’s death operations ceased entirely, ‘leaving a record in the mining archives of remarkable achievement.’ The claim was incorporated into surrounding farmland. From 1989 L&M Mining Limited reopened some Nokomai mining sites and, using new technology, achieved some good returns. In 1990, the sod raceman’s hut on the Roaring Lion Race was restored with the help of volunteers, Department of Conservation and the 1990 Commission. In the 2000s, the landowner (supported by the Department of Conservation) built a private trail – called the Roaring Lion Trail – on private land designed as a single track, cross country mountain bike/hiking trail. The trail has been hand built along the course of part of the Roaring Lion water race, preserving and recognising the historic and archaeological features along the way. In 2017, the trail can be booked for walking and biking, and the former raceman’s hut can be booked for overnight accommodation. There are plans to extend the trail to include features at Donkey Flat, recognising the importance of this historic landscape.

Current Description Sew Hoy’s workings at Nokomai and the associated race system show the technologies associated with hydraulic sluicing. Hydraulic sluicing leaves a particular pattern of archaeological evidence – a system of water races, water storage features, and gold workings, as well residential areas associated with working the claims. Ground and hydraulic sluicing took over from the cradle and pan. Hydraulic sluicing required more head (water pressure) – large races were built to bring water to the working face. The working face of the claim was worked with a high impact water jet directed from a moveable nozzle. The gold was recovered by directing the water-borne mixture of soil, stones, and gold down a channel. Gold was collected in sluice boxes (riffles) in the base of a channel while other detritus was discharged downslope or into an adjacent river or stream. Sew Hoy’s Workings and Water Race System provides an outstanding example of a race system and workings associated with hydraulic sluicing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Sew Hoy’s workings and water system are part of the wider Nokomai and Upper Nevis mining landscapes – which include other race systems and gold working sites. The Physical Evidence at Nokomai There were two separate phases of mining in the Nokomai valley – the 1860s gold rush and minor tunnelling of the 1880s; and the major workings initiated by the Sew Hoys in the mid-1890s using hydraulic elevators followed by the steady development of hydroelectric works and the attempt at dragline dredging in the 1930s. What follows is a description of the sites associated with Sew Hoy’s workings, summarised and edited from Hamel’s 1989 report. Sew Hoy’s Workings: The Race Systems Roaring Lion Race (NZAA Site F43/108, Item No. 2 on Extent Map) The Roaring Lion Race (built 1898-1901) picks up water out of the Roaring Lion Creek on the eastern slopes of the Upper Nevis Valley and carries it over 40 kilometres to the Nokomai Valley. The now dry race runs south-west along the eastern slopes of the Upper Nevis Valley, stone-lined in places and with pipes across some sidlings, to the sluicings on the Nevis-Nokomai Divide. The race is carried down the west side of the Nokomai Valley, traversing the Divide to avoid the eastern tributaries of the Nokomai River. The bench of the Roaring Lion Race averages about three metres across from the track on its berm to its uphill edge. The berm is about one metre across the water channel and averages 70-90 centimetres wide by 50 centimetres deep. In the 1920s, the Roaring Lion Race delivered water to the No.1 Race that combined the water from Diggers Creek coming in over a saddle from Garston in a head race, providing sufficient height for 560 feet of head to the elevators on the flats below. Pipes were laid for the first one to two kilometres on ledges around bluffs and across scree faces. There are hut sites associated with the race, including Forge hut, which includes a blacksmithing area and assorted metal and timber near the remains of a sod and brick hut. Surface finds of sherds of Chinese ceramics and glass have confirmed that this was a place where the Chinese builders of the race made up the pipes used for the head of the race. The race runs out of Nokomai Station into Glenfellan Station and begins to contour around the western side of Nokomai Valley and drop from the 1,005 metre contour to 975 metres a.s.l. (It moves over from the western slopes of the Garvie Range to the eastern slopes of the Nokomai Range.) On the south side of the Garston saddle, the race sets off along a scrub-covered hillside of the Slate Range to end above the remains of the great elevator hole just north of the Nokomai homestead, running parallel and just above the other big race coming in over the saddle from Diggers Creek. There were racemans’ huts along this section, the last of which was probably occupied by a Chinese raceman called Sue Moon, who was known to have a garden irrigated from the race. The restored raceman’s hut (F43/2) sits 10 metres above the race, and is of earth construction with a corrugated iron roof. Chinese ceramics found at the site confirm Chinese occupation. The walls were rebuilt and the structure re-roofed. The Roaring Lion race continues south. Above the main elevator hole there are numerous sections of edge-stacked revetting leading the race into and out of gullies and around bluffs. The remains of the lines leading down to the elevator lie in channels in about four different places on the hillside. Some water was carried sideways at low levels to carry out some hillside sluicing. Some of these spectacular sluice faces are visible from the road near the Nokomai homestead. They are considered to have been worked in the 1870s by the Nokomai Mining Company. The Roaring Lion Race is still close to the 460-metre contour above these sluicings, and since the Nokomai Flats are at about 260 metres a.s.l., the race could easily have provided the 560 feet (170.6 metres) of head described in the Mines Department reports. The race system on this part of the hillside is very complex but there seems to have been at least one C-shaped hillside reservoir. Diggers Creek Race (Site 22 on Extent Map) Often described as the Fosters Creek Race, the history of this race is not as clear as that of the Roaring Lion. It seems to have been in existence at least from Fosters Creek by 1887 and is reported to have run water down the west side of the Slate Range to Paddys Alley as well as across the Garston Saddle into Nokomai. Most of the race is marked on the cadastral maps (S151, 1979). When the Sew Hoys began hydraulic elevating in Nokomai in 1894 they found they did not have enough water and the warden reported that they put 30 men on to building a race which by elimination must have been the Diggers Creek Race, presumably the extension from Fosters Creek and probably an enlargement of the whole length of the race. This race is notable for the major siphons along its length, particularly in Fosters Creek. The section of the race from Diggers Creek to Fosters Creek is clearly visible on the western slopes of the Nokomai Range as seen from State Highway 6. The siphon bringing water from Diggers Creek across Fosters could not immediately rise to the level of the older race out of Fosters, which runs back out of Fosters Creek at a higher level. This higher branch has to wind its way from Fosters Creek into two major gullies before coming out on the face above the siphon from Diggers Creek. The Fosters Creek branch of the race continues around a very steep hillside, so sheer in places that the race had to be supported with revetment work and has large stone slabs lying edge on to support the upper walls. Once it gets round onto the main slopes running down to the Mataura Valley it begins to approach the main race from Diggers Creek. Before the junction, there was a raceman's hut. The dated beer bottles found at the site of the 1930s could well date from the last years of the raceman's occupation. Both branches of the race cross the Nevis-Garston Road, and stone revetting marks the site of the old culvert for the upper one from Fosters Creek. The race continues around scrub-covered slopes, becoming larger and deeper - 1.5 metres wide and 1 metre deep, with a ridge up to 2 metres wide on the downhill side. About half way between the last hut and Garston Saddle, the race builders felt a need for a stone-lined spillway to control the race. Unlike the Roaring Lion race, the Diggers Creek Race crosses the Garston Saddle into the Nokomai Valley in a channel rather than a siphon. It sidles round the hill face to above the elevator hole in Lion Paddock about 30 metres below the Roaring Lion Race and 168 metres above the workings. Since it was an earlier race it was probably used for the pre-Sew Hoy workings on the flat. Other Race and Dam Systems The other major water source for the Sew Hoys was the Nokomai River itself, dammed at the foot of Donkey Flat and carried downstream in a complex of races and siphons. The Copeland family built a reservoir in the head of Victoria Gully, filled by races coming from both major headwaters of the Gully. The sluicings at Sandys Creek seem to have been worked with small races brought in from gullies both to north and south. The Donkey Flat Race System (NZAA Site F43/112, Item No. 5 on Extent Map) This was a low-level race system linked to the Roaring Lion and carrying water mostly for Sew Hoy's workings in Victoria Gully and the Lion Paddock. At first, in 1894, the Sew Hoys used the existing race from Fosters Creek for their workings, extending it about five kilometres to Diggers Creek. When this proved insufficient, they tapped the Nokomai River at Donkey Flat with another five kilometres of race in 1896, at first without bothering with a dam. This race could provide only about 250 feet of head at Victoria Gully, though it must have provided 400 feet of head at Lion Paddock and may have provided the water power for the small powerhouse at the head of the flat. The Workings Below Donkey Flat Dam On the true right of the river there a complex of tailings, pipes, a possible diversion wall, and small terraces, timbers, gooseberry bushes, flat iron, stone walling and chimney bases, marking the sites of about four huts. About a kilometre below the dam, there is another small group of hut remains, associated with an earth wall which was probably also a diversion channel. There were about four huts. Rather than just being racemen, the occupants presumably worked the river bed just upstream, diverting it with a 10-metre long wall and revetting the river edge. The river falls rapidly leaving the old race high on the hillside so that it has to run well back into O’Briens Creek. The creek divides low down and the race had to be carried across two branches. Where it crosses the southern tributary, a raceman's sod hut had been placed on a terrace cut out of the hillslope above the race. Below the Shark Bay Creek confluence the Donkey Flat race continues high on the true right until it reaches a spur before the next major tributary (unnamed). Here there is a network of races, tracks and an old siphon line from which all the pipes have been removed but several concrete supports remain. The water from the Donkey Flat race was siphoned across the Nokomai Creek and taken round to Victoria Gully high on the true left side of the valley. There is, however, a race which continues down the true right of the valley, emerging from the unnamed creek at a level which enables it to continue at a sufficient height to enter a reservoir used to work sluicings high on the hillside north of Sandys Creek. Sluicings around Sandys Creek From north of Sandys Creek to opposite the Nokomai homestead there are alluvial deposits on the side of the valley, which contained sufficient gold to be worth building races and reservoirs. The deposits on the north side of Sandys Creek are notable for the number of races running into them and the complex reservoirs above them. As well as a race from Saddle Creek, water from the Roaring Lion race was also used, being piped down a spur, and the Donkey Flat race was extended to reach the small hillside reservoirs. The latter was also piped down the hillside to the elevators on the flats below. It may also have been possible to use water from the Diggers Creek Race by diverting some of it down Saddle Creek. Bullock Head Creek The main branch of the Donkey Flat Race runs down the true left of the Nokomai Valley and could have been used in some of the Bullock Head Creek workings. The workings at the foot of this creek include small tailings and huts seen at the mouth of the creek, the workings are repeated about 300 metres up the creek below the small clump of poplars where there are neatly stacked tailings with regular, deep, revetted tail races through them and a revetted race above them. The dense matagouri scrub makes it difficult to follow the subsidiary races. Victoria Gully There are tailings on the flats all the way up Victoria Gully from its wide confluence with the Nokomai River to where it enters two steep tributaries coming out of gorges. Below Commissioners Creek there are only amorphous tailings widely dispersed on the flats. Above the confluence with Commissioners Creek there are tailings and remains of residence areas and gardens, including the remains of the Copeland homestead (Norman Copeland was a long term Nokomai resident and worked for Sew Hoy in the 1930s). Up valley from the Copeland homestead, there is another elevator pond which was worked by water brought down from the Copeland reservoir. The race is small but ends about 45 metres above the valley floor, where a trace of the pipeline falls straight to the pond. Heavy tailings, some of them hand stacked, and sluicing scarps cover the valley floor up to the junction of the creek known as The Moa. Above The Moa confluence, parallel tailings formed by sluicing the terrace enclose the remains of at least two stone house ruins. Upriver the stream curves sharply around a bush-covered spur, at the foot of which is a complete set of workings - race, reservoir, two small huts, tailings, revetted tail race and one sluice face. Above this small site, the river runs within steeply dissected banks, well covered with beech forest. At the junction of two main branches, there is a high terrace on which the Copelands were able to build a reservoir by using siphons to bring the water across the gorges. The reservoir and its siphons are remarkably intact and form quite an elaborate structure. The Chinese Burial Ground (NZAA Site F43/146, Item 19 on Extent Map) The Nokomai Valley widens south of the spur where the Donkey Flat race siphon crossed at and the valley swings west in an arc around the mouth of Bullock Head Creek to low wide terraces. A Chinese burial ground is located north of where Bullock Head Creek emerges from the hills. This small burial ground is located on a gentle slope facing down the valley and consists of a single row of about five grave mounds covered with grass and a few shrubs of matagouri. There were once two marble headstones and three wooden ones (though the Lumsden burial register records six burials). The burials started just after the Sew Hoys arrived and continued through their era. The valley floor is relatively wide below the burial ground and has been intensively grazed and it is likely that there were more house sites. Races meander across the river terraces north of the Bullock Head Creek confluence to small sluice pits and tailings on the edge of the river south of where the farm track crosses this creek. There are at least three houses, poplars, and tailings typical of a hydraulic elevator but no pond. Another sunken house was found on this section of the flat, similar to the ones above Shark Bay Creek confluence where sluice pits seem to have been made use of, by revetting the walls and probably roofing with timber rafters and thatch, canvas or tin. Down the flat from it and tucked neatly into a curve of the hillslope is one of the best preserved small houses in the valley, consisting of the remains of two small buildings with a croft yard around and behind them. The simpler structure is assumed to be a barn and the one with a chimney to be a house. The Hamlets of Upper Nokomai Valley Below the flat the Nokomai River meanders, creating small flats against the hillslope of the south east side of the valley. On three of these small flats and at the mouth of Victoria Gully there are traces of small groups of dwellings. Each is marked by clumps of old crack willows and Lombardy poplars. A scatter of artefacts near one site included pieces of a ginger Jar and a rifle bar, indicating a Chinese miners' settlement. About 200 metres down the valley on the next flat, there is a complex site consisting of three stone heaps at the northern end of the flat, probably marking the chimneys of small huts, and a sod-walled complex of at least five buildings up on the terrace above the road. There was no sign of Chinese ceramics and the possible long-drop toilet suggests European occupation. The next hamlet is less well marked but the names School Creek and Blacksmiths Flat, along with old trees and a concrete chimney suggests another hamlet. The river flats have been so disturbed by flooding that it is difficult to discern patterns of mining. Only three of nine hydraulic ponds remain, the rest having been filled by the river shifting gravel. The most interesting of the hamlets is the row of seven little houses at the mouth of Victoria Gully. The miners literally lived on top of their sluicings with the tail races running between the huts, leaving some of them up on rocky mounds. The Nokomai Valley runs through its last narrow gorge between the confluence with Victoria Gully and the homestead flats. The small river flats are heavily overgrown with broom and gorse, but in among them is another site – a small deep hole which does not seem to be a hydraulic elevator pond. A double race from the saddle ran along the western side of the Nokomai Valley, probably carrying water from the Roaring Lion to major sluicing and elevator workings on the flats. Comparisons Gold mining drove the building of the first water races in Otago. Some of these races were substantial and fed complex mining systems – examples include the Scandinavian Water Race feeding the St Bathans workings, the Carrick Race, the Mt Ida Race, the Johnston Race (over 20 kilometres long) in the Rock and Pillars that fed the workings at The Bend, and the complex series of races that supplied workings at Gabriel’s Gully. The Scandinavian Water Race brought in water from the Manuherikia River at Surface Hill 40 kilometres to the diggings around St Bathans. The race is associated with another outstanding figure in Otago gold mining history – pioneering miner and leader of the alluvial gold mining industry John Ewing, variously known as ‘Big John Ewing’, the ‘Gold Baron’ or the ‘Mining Monarch’. The Scandinavian Water Race is not entered on the New Zealand Heritage List, nor are the associated workings at St Bathans. Like the Roaring Lion Race and the Diggers Creek Race, the Scandinavian Water Race was built by private investors. Sew Hoy’s importance to gold mining is comparable to that of John Ewing – both were pivotal figures and both were involved in diverse mining investments. The Carrick Water Race, built in 1874, carries water 34 kilometres from the high western slopes of the Carrick Range, switching to the eastern slopes, and took water to the dramatic Bannockburn Sluicings (List No. 5612, Category 2). The Carrick Race itself is not included on the List. The race still carries water. The Mt Ida Race opened in 1877 and supplied water for the Hogburn Diggings. The 108 kilometre Mt Ida Race traverses the relatively flat Maniototo Plains from the Manuherikia River to the Hogburn at Naseby. The race was built to flush the accumulated tailings, and any future tailings down a new sludge channel, allowing for more mining at the relatively flat Hogburn Diggings. Its design was supervised by the Otago Provincial Engineer and was funded by the Government. The race is still running in 2016. The Mt Ida Race is not included on the New Zealand Heritage List, nor are the remains of mining at Naseby. At Gabriel’s Gully over 400 miles of water races were built to service the workings, though none as long as those at Nokomai, and they were a complex group rather than a single race. Johnston’s Race, a high race at the north end of the Rock and Pillar Range is in the headwaters of the Pig Burn. It collects water at the head of a tributary of the Cambridge Creek. The water right could have belonged to any of the three main workings at Riverslea, Hamiltons and The Beeches. Johnston’s Race is not as visible or iconic in the landscape as the other races mentioned above.

Public NZAA Number

F43/108

Completion Date

17th January 2018

Report Written By

Heather Bauchop

Information Sources

Hamel, 1989 (2)

J. Hamel, 'Survey of Historic and Archaeological Sites on Nokomai Station and in the upper Nevis Valley', July 1989

Hamel, 1991 (2)

Jill Hamel, 'Gold mining in the Nokomai Valley: A second report', May 1991

Ng, 1993

Ng, James, Windows on a Chinese Past, Volume 1, Otago Heritage Books, Dunedin, 1993

Ng, 1995

Ng, James, Windows on a Chinese Past, Volume 2, Otago Heritage Books, Dunedin, 1995

Ng, 1999

Ng, James, Windows on a Chinese Past, Volume 3, Otago Heritage Books, Dunedin, 1999

Te Ara - The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

www.TeAra.govt.nz

Report Written By

A fully referenced New Zealand Heritage List report is available on request from the Otago/Southland Office of Heritage New Zealand. Disclaimer Please note that entry on the New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero identifies only the heritage values of the property concerned, and should not be construed as advice on the state of the property, or as a comment of its soundness or safety, including in regard to earthquake risk, safety in the event of fire, or insanitary conditions. Archaeological sites are protected by the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 2014, regardless of whether they are entered on the New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero or not. Archaeological sites include ‘places associated with pre-1900 human activity, where there may be evidence relating to the history of New Zealand’. This List entry report should not be read as a statement on whether or not the archaeological provisions of the Act apply to the property (s) concerned. Please contact your local Heritage New Zealand office for archaeological advice.

Current Usages

Uses: Cultural Landscape

Specific Usage: Industrial/mining landscape

Uses: Transport

Specific Usage: Footpath/Path/track

Former Usages

General Usage:: Mining

Specific Usage: Alluvial Workings

General Usage:: Mining

Specific Usage: Elevator hole

General Usage:: Mining

Specific Usage: Mine reservoir/ dam

General Usage:: Mining

Specific Usage: Mine Water Race/ Water Race cuttings/tunnels etc

General Usage:: Mining

Specific Usage: Mining camp/settlement/housing

General Usage:: Mining

Specific Usage: Sluicing Hole/Area

Themes

Web Links

description: Choie Sew Hoy’s Family Tree

url: http://www.choiesewhoy.com/pdf/choiesewhoy-familytree2.pdf

description: The Sew Hoy family

url: https://www.rnz.co.nz/national/programmes/asianreport/galleries/sew-hoy-family

description: ROARING LION, HIDDEN GOLD

url: https://www.nzgeo.com/stories/roaring-lion-hidden-gold/

Stay up to date with Heritage this month